|

It would have been impossible to conduct an expedition to Finnmark centred around the

environment and omit the story of the Sami, the first population to truly settle this wild region. Today, Sami flags are flown proudly in Finnmark. The striking red, green, yellow and blue background, adorned with a red and blue motif representing the sun and moon, stands in sharp contrast to the ‘Nordic Cross’ style national Norwegian flag. Indeed, the cross of the Norwegian flag, representing the country’s Christian routes, and the sun and moon motif of the Sami flag, heralding from local Shamanistic religion, might seem to be polar opposites. Yet the two are frequently seen together, representing a unique blend of regional and national identity. Sami emblems hang behind campsite reception desks, yet the staff made it clear that they were proud to be both Norwegian and Sami. However, this was not always the case. Faced with ‘Norwegification’ efforts from southerners seeking a modern Norwegian nation-state in the mid to late nineteenth century, the Sami are no strangers to the struggle to preserve cultural autonomy and identity, of which the environment forms a major theme and sometimes battleground. Christianity competed with Shamanism, whilst a linguistic battle raged over the introduction of the Norwegian language. The Sami emphasis on the omnipotence of mother earth and the seas clashed with rival ideas that land could be owned, bought and sold. Despite these conflicts, the Sami have succeeded in protecting and celebrating their ethnic identity and this is in no small part thanks to their relationship with the environment. This can be seen in what has been immortalised in local memory as the ‘Alta Affair’. In 1978, a hydro-electric dam approved by the national Norwegian Parliament on the Alta-Kautokeino River, flowing through Sami territory, threatened to damage the village of Máze as well as disrupt salmon and reindeer migration patterns, both core environmental components of the Sami lifestyle. Despite extensive civil disobedience and hunger strikes, the plant was completed in 1987. However, such Sami resistance to intrusion in the environment did not go unheard. In 1988, an amendment to the Norwegian Constitution was made. It read “It is the responsibility of the authorities of the state to create conditions enabling the Sami people to preserve and develop its language, culture and way of life” 1 . A new Sami Parliament opened in 1989, followed by full recognition of the International Labour Organisation’s International Convention on Indigenous Populations by the Norwegian government in 1990 2 . As a result, environmental issues have provided a mouthpiece for the Finnmark Sami population at large and have paved the way for increased cultural and social autonomy for this ancient people. The story of the Sami commitment to the environment certainly proved inspiring, given our similar interests in vegetation and climate change in the region. People we met who identified as Sami proved ever helpful and hospitable. We were treated to primary oral recollections as to how the region had changed and popular sentiment regarding such change. It’s safe to say we’ve all found it a privilege to study climate change in an area where there is such cultural engagement with the environment. 1,2 Fonneland, Trude (1977) Contemporary Shamanisms in Norway, Oxford University Press. Page 8.

1 Comment

Whilst (thankfully) personally never having been in a situation where an EpiPen was an essential

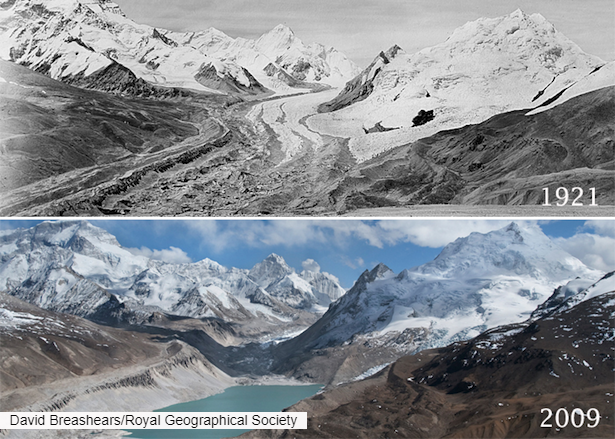

immediate course of action, any fan of sustained periods in the outdoors or abroad will insist that such items are indispensable. The EpiPen is the ultimate example of ‘I’d rather have it and not need it, than need it and not have it’. Indeed, I have no regrets in admitting that it was with this rationale in mind that I, as Expedition Medical Officer, went about the task of assembling a comprehensive (yet somewhat financially viable) medical kit for our expedition to Arctic Norway. The final collection of dressings, painkillers, ointments and dressings ensured that we as a team were comprehensively prepared for the trials the Arctic might have imposed upon us. My primary inspiration and direction came from a comprehensive Royal Geographical Society wilderness medicine training course I attended between the 15 th and 16 th of May, 2018. Myself and fellow team member Olly Rice left Oxford for a warm break in central London, where we were given a crash course in everything from altitude sickness to snakebites. The course even provided us with party bags; all attendants were given a USB stick containing useful PDFs with further information and basic kit plans. I also made the decision to arm myself with the reassuringly thick book: The Oxford Handbook of Expedition and Wilderness Medicine, which adds even more information to the mix, even containing a reassuring section on basic dentistry! The RGS Course and the Expedition Handbook pushed the same key themes. Firstly, prevention is better than cure. Dehydration and blistered feet (at risk of infection) can be avoided through regular water breaks, good boots and an ample supply of blister plasters for example. Secondly, it quickly became apparent that wilderness medicine is less about helping people to get better; rather, it is primarily concerned with stopping people from getting worse. Looking at my frightening selection of bandages, slings and limb splints prior to departure reiterated that the purpose of this kit was to prevent the transition from bad to worse. At the stage when a limb splint becomes vital, so does prompt evacuation from the field. As a result, medical planning hammered home to me the importance of sound planning and a reliable escape plan. Medicine, safety, and organisation, it seems, are all synonymous. Matt My favourite part of preparing for this summer’s expedition has definitely been hunting for old photographs to retake for our rephotography project. As a team, we wanted to find a way to clearly demonstrate to the public that environmental change is occurring, and reproducing old photographs seemed like an obvious choice. Everyone has seen sets of photos showing how rapidly ice is retreating in many areas of the world, such as this photo of Mt Everest by George Mallory, reproduced years later by David Breashears. The changes in vegetation that we will see over the last 50 years in Finnmark will be far less dramatic, but should still be visible. Before first heading to the Varanger Peninsula in 2016 we were told stories of waist-high brush, which decades later has changed into small birch trees. Comparing similar photos from 1974 and 2016 gives an indication of the changes that we will see. In the photos below the red arrow marks the same point in each photograph. Changes can be seen, and it will be exciting to return to the area and retake the photos properly. Tracking down old photos from such a remote area has been challenging at times, but a fun treasure hunt. Oxford University has a great history of sending expeditions to the area over the years to look at the interesting geology. I have very much enjoyed connecting with the members of these expeditions and others, who are now distributed far across the world. They definitely have some stories to tell and hold the area close to their hearts, making me look forward to our coming expedition even more.

Roughly 300 emails later I’ve found about 80 old photos of the area showing vegetation, and there are more to come. Now we’re left with the challenge of trying to locate these as precisely as possible. We can then narrow down the correct view when in the field, and reproduce some of the beautiful photographs that I’ve been given. Hopefully they will provide us with a different insight into how this landscape is changing through time. Holly We will be researching, living, eating, sleeping, everything-ing together for five weeks on the remote Varanger Peninsula bringing together a team with a wide variety of scientific and outdoor experience. Whilst we can buy the tents, flights, and drones necessary to facilitate this (thanks to the generous support of our funders), there is one thing we cannot buy but is crucial to the expedition’s success - teamwork.

This is why over the Easter holidays four members of the team got together for a venture to the Lake District. The Lake District is perhaps one of the closest landscapes in England to match what we will experience in Finnmark with lushous hills, rocky slopes, rivers, and temperatures ranging from -5 to 20 degrees centigrade. To scope our outdoor expertise and bond as a team we woke early the first morning to hike the snow-topped Helvellyn, the foot of which we camped at that night. The day tested us not just in fitness but navigating a path covered by the snow, avoiding the whitened cliff-edges as we traversed. Hiking up a wet, rocky, wind-riven slope by ourselves is one thing, but in Finnmark we won’t have the opportunity to simply leave the stuff we don’t need in the car. So to approximate our forthcoming challenges as best as possible the hike was accompanied by the full set of supplies, clothes, tents, and equipment for the whole Lake District venture. Though challenging, we had a fantastic time getting to know and support one another as a team in the field. At the end of the first day despite ascending and transcending Helvellyn, we travelled to the other side of Grasmere to hike a further 5 miles to a sport by a tarn to wild-camp for the night. Wild-camping will be our accommodation for the whole period carrying out research in Finnmark. Despite temperatures plummeting to below zero and waking up to a frozen tarn, that night we were treated to a full starry-sky as we cooked dinner in the dark over a gas-lit stove. It’s moments like that stay with you. Though the next day was windy, wet, boggy, and remote, surpassing what we expect to be an average day on the Varanger Peninsula, we took it in turns to navigate across less-trodden paths. We crossed rivers, passed spectacular frozen waterfalls, and culminated in a steep rocky descent at the head of a glacial valley. These few days were perhaps some one the most important we have spent together as a team so far. Coming together helped us understand the strengths of our equipment and our team looking forward in a way none of our regular team meetings in Oxford could. It made the expedition feel real and exciting. After our venture to the Lake District it is clearer than ever that despite our varied experience from fells to rainforests, we can work as a successful team in Finnmark. Olly |

Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed